At least some of the government’s ammunition for such drastic cuts to the small-scale feed-in tariff earlier this year was the continued fall in costs the technology has been enjoying in recent years. So imagine the scenes in three Whitehall Place when its cost of install figures were crunched in June.

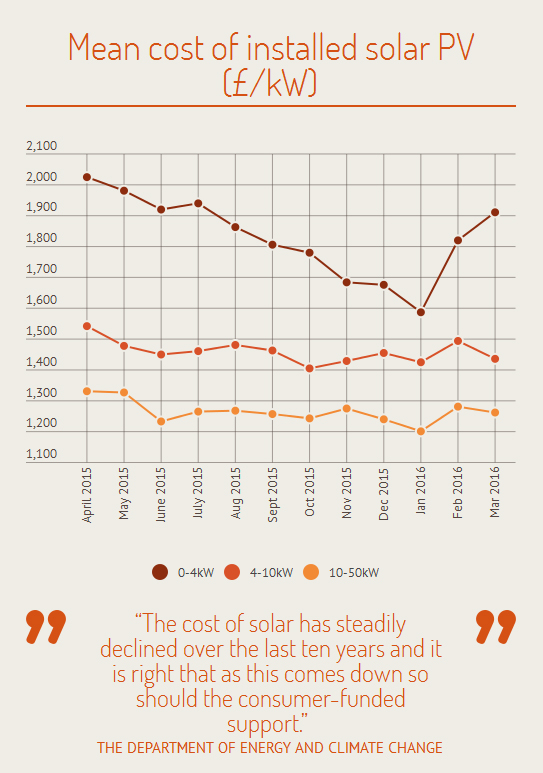

Those figures showed that the average cost of a 3kW domestic solar installation was nearly £1,000 more expensive in March than it was in January this year, having steadily fallen over the course of 2015. Costs for 0-4kW installs are now around the £1,900 per kilowatt mark, drastically more than the £1,587/kW average recorded in January.

That increase not only raises questions about the wisdom of DECC’s FiT cuts, but also the validity of its current FiT rate.

One of the key assumptions in Parsons Brinkerhoff’s report of the feed-in tariff, used to design the new regime that saw domestic rates fall to as low as 4.39p/kWh, was the average CapEx of £1,630/kW for solar PV under the 0-10kW band. Those rates have been designed specifically to achieve a targeted return on investment of 4.8%. Such a sharp increase in costs of installation would therefore fail to guarantee consumers the return DECC set out to achieve.

When questioned by sister publication Solar Power Portal on the data release, a DECC spokeswoman said: “Our priority is to keep energy bills as low as possible for families and businesses whilst supporting low carbon technologies that represent value for money.

“The cost of solar has steadily declined over the last ten years and it is right that as this comes down so should the consumer-funded support,” the spokeswoman said.

DECC would however not be drawn on the potential implications of surging install costs on available returns.

The industry’s response made it clear that DECC had been forewarned of such a possibility. “We know from our current survey work that some companies are struggling to survive, so every sale matters. The profits on a single install are often pretty modest, so companies need volume for low project returns to make sense.

“It is too early to draw conclusions, but we have always warned that low cost solar depends on a volume market. Maintaining cost reductions requires investment, and that was why we set out a steady glide path to parity for solar in our Solar Independence Plan that would give companies the forward vision necessary,” Leonie Greene, head of external affairs at the Solar Trade Association, said.

But what could cause such a stark increase in costs, when previous trends have only been downward?

““The fact is, materials and installation costs at the end of 2015 were pretty much as low as they could go…There was very little ‘fat’ left in the chain.”

Andy O’Leary, Sibert Solar

Cause and effect

It stands to reason that as volume has fallen, installers have had to prop up their businesses through increased labour costs per install. As Greene says, the volume market is crucial to solar’s cost curve and a reduced uptake would only send prices one way.

Installers are not the only ones feeling the pressure however. Suppliers and distributors are experiencing the exact same downturn and while not as exposed to the cuts’ effect on any one single technology, will be subject to price pressures as much as the next cog in the supply chain. Gareth Jones, chief executive at installation firm Carbon Zero, says that he has seen module costs rise by between £10 and £15 per panel, which would immediately add an extra £200 to each typical install. Associated equipment costs have also increased.

Sibert Solar’s Andy O’Leary says that DECC failed to factor into its cost assumptions that the collapsing demand would counteract the economies of scale installers had previously been able to enjoy. “The fact is, materials and installation costs at the end of 2015 were pretty much as low as they could go, given the MIP environment and supply-line structure.

There was very little ‘fat’ left in the chain,” he says.

What the department will now have to contend with however is any potential underspend this causes further down the line. While DECC’s FIT review was designed as a cost control measure to tackle an overspend under the Levy Control Framework, the rates and deployment caps have been designed to spend precisely the finance allocated to it. Deployment under the new regime has so far been far below expectations and should it continue to falter, it will raise yet more questions over the much-vaunted LCF overspend.

LCF spending is already in doubt after a third of the five solar projects handed a Contracts for Difference had its subsidy withdrawn in March, with a further project also facing severe delays. The £2 billion Neart na Gaoithe wind farm also had its CfD withdrawn in May.

Former energy secretary Sir Ed Davey has long argued that one of the principal faults in the LCF is the assumption that all projects handed subsidy contracts will go ahead. The impact of June’s Brexit referendum has also resulted in speculation that inward investment could be disrupted, placing other renewable energy projects at risk.

The total of that underspend could soon rack up.

The cancellation of wind and solar CfD projects, coupled with flagging deployment under the new FiT regime, would therefore create room under the LCF spending cap for a potential increase in feed-in tariffs needed to stimulate deployment. DECC also has the policy to do so under the FiT review which included a budget reconciliation clause, pledging to biannual reviews of the tariff and expenditure.

DECC continues to monitor the number of installations made under the new regime, but an intervention would be considered unlikely given the department’s desire to allow the tariffs time to bed in. Robert Ede, energy and environment specialist at consultancy group The Whitehouse Consultancy, said it remained unlikely that the government would change the feed-in tariff with other policies currently drawing its attention, but stressed that action was required all the same.

“Recently, Andrea Leadsom stood up in parliament and stated that the government expect rooftop deployment to increase as the industry acclimatises to the new tariffs. However the recent installation data suggests this is a remote prospect. Will DECC be persuaded to take a fresh look at the FiT? Despite recent developments on CfD contracts, this seems unlikely.

“A more profitable route for the industry could be to work alongside the government in opposing the minimum import price (MIP), currently under review by the European Commission. Whilst much of this will depend on the referendum outcome, the removal of the MIP would bring substantial cost savings for installers – and give a significant boost to the UK residential market if we decide to stay within the EU,” Ede said.

This story originally appeared in Issue 1 of Inside Clean Energy magazine. Fill out the form below to download the entire issue for free.